Alice Koeth

a.k.a. ALICE, 1927–2020

This is a living and breathing tribute page to honor a legendary calligrapher and one of NYC’s very own. Please check back as we fill it with memories, photos and words about the wonderful woman that was Alice.

by Jerry Kelly

Today probably every member of the Society of Scribes is familiar to some extent with Alice, one of our founding members. She is perhaps our most important founding member, for from the start Alice took on a lion’s share of the work involved in establishing the SOS and keeping it afloat in the crucial early years. Alice created the Society’s original logo (still in use) and designed its stationery. She contributed regularly to its annual Engagement Calendars. She was curator, along with me, of the Society’s 25th anniversary exhibition in 1999, held at the American Institute of Graphic Arts (AIGA). She ran rings around me, doing much of the work, including designing the invitation and logo for the show.

The impetus for Alice’s interest in fine writing is unusual: in sixth grade she got a “U” (unsatisfactory) in penmanship. This did not go over well with her demanding, perfectionist father (who, by the way, had excellent handwriting). He told her “if you can draw pictures, you can draw letters.” She put her mind to improving her handwriting, and got an “A” on the very next report card.

A turning point in her life came in 1947 when she heard of a series of lectures on “The History of the Alphabet” given by Arnold Bank at the Art Students League. She attended the talks and, as she put it, “walked into another world.” In January 1948 she registered for Bank’s night classes at the Brooklyn Museum Art School, all the time commuting from Staten Island. The classes ran from 7 pm to 10 pm, three nights a week.

Alice Koeth was born in Manhattan on December 2, 1927. She lived with her parents and siblings at the family residence in Staten Island until moving on her own to Manhattan in the 1950s. Going back and forth on the Staten Island Ferry remained (along with traveling on the Third Avenue El ) the constant rhythm of her young years. She attended Washington Irving High School, at that time a vocational school for girls; it took her two hours each way.

Before becoming a freelance calligrapher, Alice worked in cabinetry, cutting by hand intricate inlays of wood veneers for tabletops and cabinet doors in the shop of Andrew Szoeke, who also did design work and lettering for advertisements for Saks Fifth Avenue. Later she worked in production at Pocket Books. “I did a lot of different things, not only lettering. I did book jacket design, interior book design, and some illustration. If it needed a drawing, I made a drawing. If it needed a photo, I took the photo. If it needed layout and type, I did that – it was the whole package.”

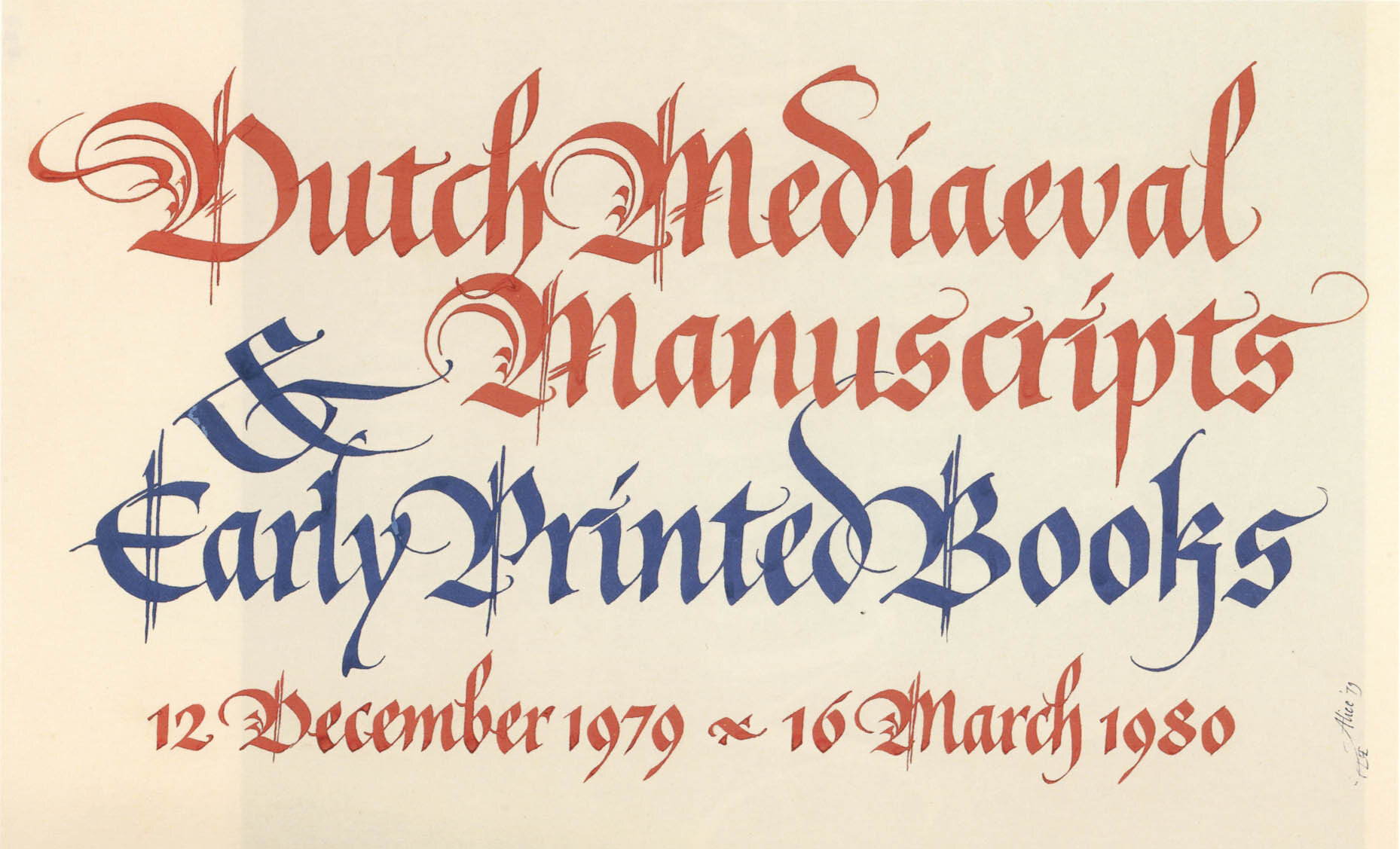

Starting in 1953 she began a long period of freelance work. In 1969 she worked for several months as a layout person at the John Stevens Shop in Newport, Rhode Island. For more than three decades, starting in 1967, she designed and wrote the highly praised signs for the Morgan Library. Many of us would spend a good deal of time outside the museum, staring at Alice’s posters, before going inside to see the exhibition. Sometimes I spent more time looking at Alice’s posters outside than viewing the exhibitions inside!

Early on she dropped her last name and signed her work with just her first name, Alice. She did this because she became tired of people mispronouncing her last name, which, if true to its German origins, would be pronounced more like “Kert,” although her family pronounced it “Kayth.” Even Alice’s father and his brother could not agree on the pronunciation! As an artist working under her first name only, she foreshadowed Twiggy, Cher, and Madonna by many years.

“As a teacher, Alice is the whole package: she has a deep knowledge of the history and practice of letters and calligraphy, the skill to match, and an enduring fascination with writing implements: how they’re made and how they work”

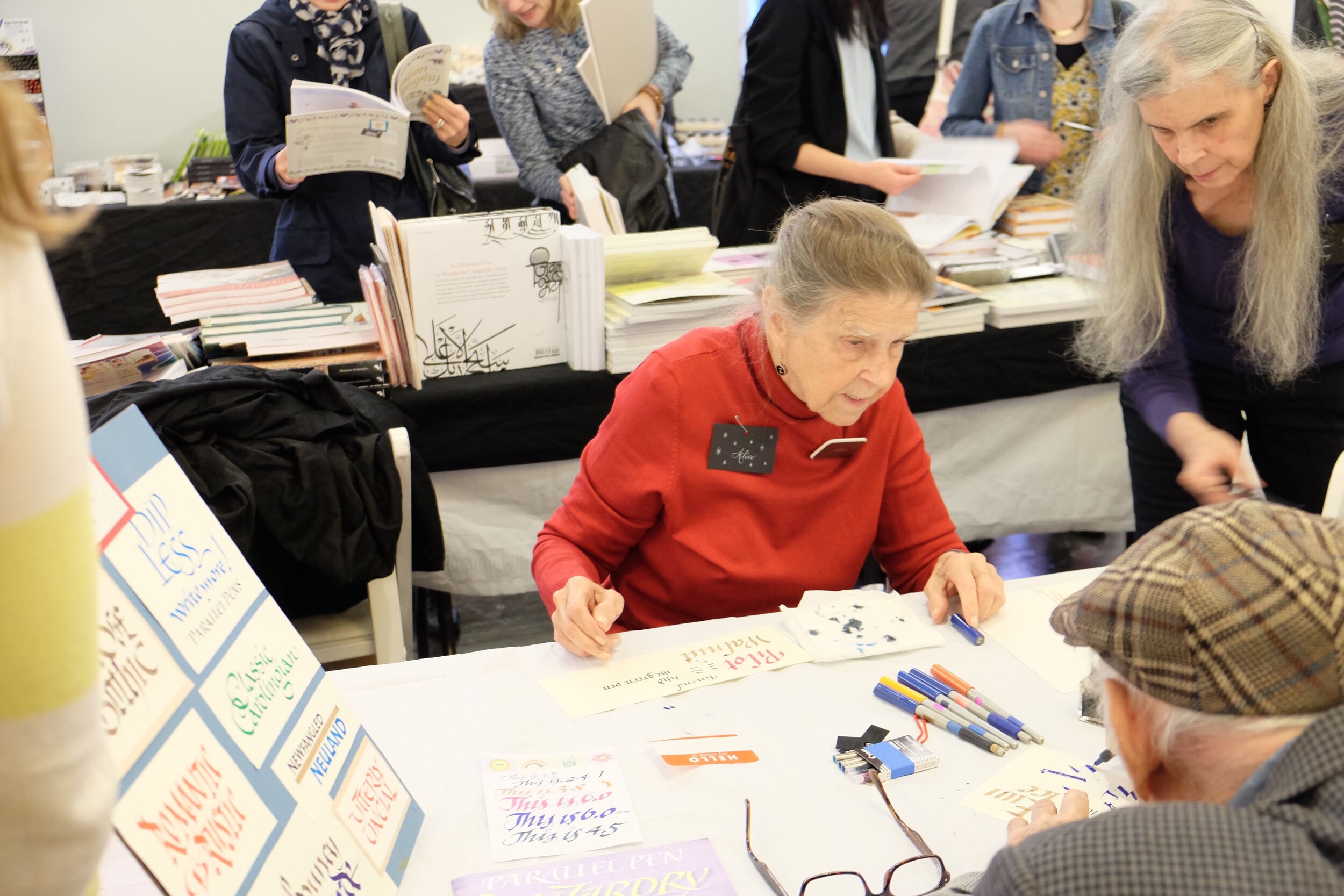

Not to be overlooked is Alice’s work as a teacher. From workshops at calligraphy conferences and other venues to regularly scheduled (though non-credit) classes at Columbia University’s School of Library Service, the Society of Scribes, and elsewhere, she has inspired legions of scribes. Calligrapher Anna Pinto has written: “As a teacher, Alice is the whole package: she has a deep knowledge of the history and practice of letters and calligraphy, the skill to match, and an enduring fascination with writing implements: how they’re made and how they work. Donald Jackson once said, ‘you can’t expect to get good results in your work if you don’t use good materials’ – well, Alice takes good materials and makes them better! Slicing a slit into the corner of a Coit pen with a jeweler’s saw and then polishing it so that it will give the beautiful hairline flourishes so evident in her posters for the Morgan – this is just one of the many tips and tricks Alice has shared with her lucky students.”

Alice and Hermann Zapf

Alice and Sheila Waters in 2016

Making images with a broad-edged pen became something of a specialty for Alice. She has said: “As they certainly knew [in Asia], calligraphy is the art of line. The same line that draws a flower draws a letter. The reason I think that people can draw letters a little easier than a flower is because they are more familiar with letters, not because the broad-edged pen technique is different.” She frequently taught workshops on this facet of a calligrapher’s repertoire.

Still, it is for her beautiful writing that Alice is justifiably best known. Her style sets her apart, and her work has long been admired by calligraphers all over the world. The variety of Alice’s scribal work is impressive. She used a wide assortment of other hands and “made them her own” (as Edward Johnson said). Her variations on black letter are comparable to those of the German and French masters from the golden age of calligraphy. Other scripts, such as rustic, uncial, and Spencerian appear less frequently, but are used when appropriate. All were always executed with consummate skill. Even though broad-edged pen writing is a hallmark of her work, she occasionally employed beautiful built up lettering.

For pure writing, where a broad-edged pen in the hand of a master produces modulated strokes in an aesthetic manner that is unique in art, Alice’s work is unsurpassed. What is most uncommon was her ability to handle the pen so deftly in both small and large writing: most scribes are good at one or the other, seldom both. For calligraphy at text size, or exceptionally large display sizes, such as her much admired posters for the Morgan Library, the penwork shows all the beauty and subtlety of a well-handled broad-edged tool.

A seldom noted aspect of Alice’s calligraphy is her thorough study of historical hands. Alice summed up the historical basis of her work this way: “Once you get the fundamentals, put your own spin on it; change it knowledgeably by studying historic facsimiles so you don’t end up ‘looking like’ or being part of a school. One shouldn’t be able to be pegged in a particular teacher’s mode.” A student, Cari Ferraro, recalls that in class Alice “always stressed that we begin from a strong historical basis. We can modernize a style, but to truly understand it, we need to look at the original manuscripts. This love of history imbues all her work.” When asked where such references to early calligraphy come from, Alice immediately answers: “Arnold Bank,” her teacher. Bank had a vast knowledge of paleography, in addition to being an accomplished scribe. Yet of all linear / calligraphic artists, Alice most admired the caricaturist Al Hirschfeld, whose work appeared regularly in the New York Times. She says “he drew the most elegantly disciplined line. . . . I think there is no one who came anywhere near him.”

“Alice always stressed that we begin from a strong historical basis. We can modernize a style, but to truly understand it, we need to look at the original manuscripts. This love of history imbues all her work.”

In addition to historical sources, Alice has also studied and assimilated many of the best features of modern scribal work. Her work was not backward-looking; instead, it is a combination of various styles and influences, old and new, which she has absorbed into her own vigorous, graceful style.

Alice passed away early in the morning on 6 October 2020. I have heard from so many calligraphers how inspirational Alice has been for them and their work. A common statement is that “there was no one like her.” I could not agree more. To say she will be missed seems like a gross understatement, yet how else can we express how important she has been to those who were fortunate enough to have known her, and to the world of calligraphy in the twentieth century and beyond.

– Jerry Kelly

Read an interview with Alice by JoAnne Powell from a 1985 issue of the Society of Scribes journal.

Do you have fond memories or words you want to share?

Send them in below! We hope to have an in-person celebration of Alice’s life and work when we are able to, and would love to hear from you.